60 year old male executive came to me with severe anxiety. Very successful. Top of his profession.

60 year old male executive came to me with severe anxiety. Very successful. Top of his profession.

He had been married once in his 20s for several years and thereafter had a number of brief & unsatisfactory romantic involvements.

He tells me that he gets angry easily and is triggered when others express opinions that differ from his own.

He believes the partner in his current relationship is the “love of his life.” However he finds her to be very critical of him. He traces their disconnect to her difficult childhood.

However on speaking with him I discovered that he himself never effectively bonded with his own mother and father. He was one of seven children and felt like an outsider from the family system at key developmental stages. His parents seemed too busy with his siblings to take much notice of him.

At a deeper level he was like an overgrown orphan, wandering through the world in search of an identity.

His severe anxiety and depressive mood indicated that he was in hyper arousal and chronic states of elevated fight, flight and freeze. These states were propelled by his inability to attach possibly from infancy already. This meant that in his adult life he was missing out on the wonderful security afforded to us by love.

When John started his sessions his wish was for his relationship with his partner to be a safe haven, where he can express himself openly, completely, playfully and creatively. This was a new relationship and he was uncertain as to how to please his partner, his opinions and advice were not always appreciated and he was often met with impatience, ‘Your help is not help.’

Growing up in a large family with six siblings had left him feeling that his family bonds with his parents were weak. His mother was more engaged with her daughters than her sons, and his father was stern, angry and silent. His childhood felt like a perpetual winter where the need for love and belonging went unmet. In adult life he had few long term meaningful friendships. He was prone to anxiety and depression and feeling that he had never quite matured in some respects.

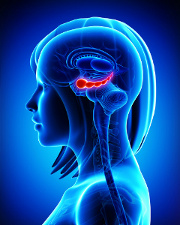

John suffered from all the signs and symptoms of a lack of bonding with his mother and father. He struggled to maintain lasting love relationships, he didn’t keep in touch much with his siblings, or his old friends. He was always moving on, rather than putting down roots. On top of that the biggest problem was his primitive survival reflex brain, called the Amygdala was dominating his behavior, and for this reason he could not experience any pleasant emotions at all.

John’s Amygdala had been activated by the stress of emotional isolation in childhood. As a result he was in a permanent state of unhappiness, anxiety and tension, irritability and he was overreacting to small upsets in his relationship. Though he realized intellectually what was happening to him, he simply could not change his reactions, even though sheer willpower.

The “Darth Vader” of the Brain: What is the Amygdala?

Traumatic and stressful experiences activate and lock in the Amygdala, a small part of our brain that produces our primal defenses of fight, flight and freeze. Once we feel we have our back to the wall and have to defend ourselves: pleasure and happiness go out the door, as do common sense and logic.

The Amygdala is also important for bonding to our mother, which is why it is so vital to balance this part of the brain.

Focusing on Stress States

Focusing on Stress States

John had never bonded with his mother when he was developing and was permanently stuck in the trauma of separation. Before he could even begin to feel whole and complete: we had to take a deeper look at his stress states of fight, flight and freeze.

Overcoming anger about emotional neglect was also a necessary part of his recovery. To achieve this he was given a custom prescription of activities that included contemplating emotions like anger and resentment, along with doing specially designed physical exercises for vision, balance and movement.

This particular combination of activities allowed him to integrate his conscious recollections with his feelings and bodily reactions. He was able to move his consciousness out of being stuck in the survival oriented Amygdala part of the brain and into the more highly developed social areas of his brain.

To make John’s wish come true and help him find lasting true love as an adult, his Amygdala had to be brought out of the high alert, defensive state. Instead of feeling threatened and afraid, he needed to feel secure. This was achieved with a series of exercises that automatically trigger a release of the stress memories. Once these stresses were released, his brain automatically re-wired itself for bonding and connection, giving John a second chance at both feeling loved and being loving.

For several weeks John was given a series of exercises that helped him to feel more bonded and attached to his partner.

The disappointment and sadness of feeling cut off from others which stemmed from his childhood years had to be processed. And special child development movement exercises triggered his brain to grow new nerve connections to balance these emotions and develop the maturities he had missed out on.

Outcome

Outcome

After several sessions he could report more happy interactions with his partner. Although short lived, this showed that his emotional bonding was improving. He found he could keep calm and not overreact to his partner’s differences of opinion and it was quite effortless. He was surprised by pleasant memories of playing ‘house’ with his younger brother as a child, and feelings of profound peace, an unusual experience for him. These pleasure states showed that his nervous system was moving towards a better balance. And he was planning a new creative business venture. Instead of thinking of throwing in the towel on the’ love of his life.’ He was settling into the comfort of a life lived together.

It’s been a Lonely Path. Find the answers you need!

Register to receive email notifications regarding upcoming live support sessions for men

with clinical psychologist Anca Ramsden.

You will also be provided the opportunity to email your personal questions to Anca.

Each week she will select one question to answer in our newsletter discussion.

Submit your own questions and also learn from what other men are posting.

All living creatures, from reptiles through to mammals, have these reflexes that help them assess and respond to threats. This is why the part of our brain that produces these reflexes is often called the ‘reptilian brain.’

All living creatures, from reptiles through to mammals, have these reflexes that help them assess and respond to threats. This is why the part of our brain that produces these reflexes is often called the ‘reptilian brain.’

The Hippocampus

The Hippocampus 60 year old male executive came to me with severe anxiety. Very successful. Top of his profession.

60 year old male executive came to me with severe anxiety. Very successful. Top of his profession.

Focusing on Stress States

Focusing on Stress States Outcome

Outcome His daughter was particularly affected. She became teary and depressed complaining of headaches after she saw her father strike her mother. She wanted her parents to sort out their problems and she wanted peace in the home, and loving relationships. Geoff doted on his daughter and for the sake of his marriage and his children, he agreed to get help.

His daughter was particularly affected. She became teary and depressed complaining of headaches after she saw her father strike her mother. She wanted her parents to sort out their problems and she wanted peace in the home, and loving relationships. Geoff doted on his daughter and for the sake of his marriage and his children, he agreed to get help.